Perl 6 Hands-On Workshop: Weatherapp (Part 2)

Read this article on Perl6.Party

Be sure to read Part 1 of this workshop first.

Imagine writing 10,000 lines of code and then throwing it all away. Turns out when the client said "easy to use," they meant being able to access the app without a password, but you took it to mean a "smart" UI that figures out user's setup and stores it together with their account information. Ouch.

The last largish piece of code where I didn't bother writing design docs was 948 lines of code and documentation. That doesn't include a couple of supporting plugins and programs I wrote using it. I had to blow it all up and re-start from scratch. There weren't any picky clients involved. The client was me and in the first 10 seconds of using that code in a real program, I realized it sucked. Don't be like me.

Today, we'll write a detailed design for our weather reporting program. There are plenty of books and opinions on the subject, so I won't tell you how you should do design. I'll tell you how I do it and if at the end you decide that I'm an idiot, well... at least I tried.

The Reason

It's pretty easy to convince yourself that writing design docs is a waste of time. The reason for such a feeling is because design future-proofs the software, proving useful after months or years, and us, squishy sacks of snot and muscle, really like the type of stuff we can touch, see, and run right away. However, unless you can hold all the workings of your program entirely into your head at once, you'll benefit from jotting down the design first. Here are some of the arguments against doing so I heard from others or thought about myself:

It's more work / More time consuming

That's only true if you consider the amount of work done today or in the next couple of weeks. Unless it's a one-off script that can die after that time, you'll have to deal with new features added, current features modified, appearance of new technologies and deprecation of old ones.

If you never sat down and actively thought about how your piece of software will handle those things, it'll be more work to change them later on, because you'll have to change the architecture of already-written code and that might mean rewriting the entire program in extreme cases.

There are worse fates than a rewrite, however. How about being stuck with awful software for a decade or more? It does everything you want it to, if you add a couple of convoluted hacks no one knows how to maintain. You can't really change it, because it's a lot of work and too many things depend on it working the way it is right now. Sure, the interface is abhorrent, but at least it works. And you can pretend that piece of code doesn't really exist, until you have to add a new feature to it.

Yeah, tell it to my boss!

You tell them! Listen, if your boss tells you to write a complicated program in one hour... which parts of it would you leave unimplemented, for the client to complain about? Which parts of it would you leave buggy? Which parts of it would you leave non-secure?

Because you're doing the same thing when you don't bother with the design, don't bother with the tests, and don't bother with the documentation. The only difference is the time when people find out how screwed everyone is is further in the future, which lets you delude yourself into thinking those parts can be omitted.

Just as you would tell your boss they aren't giving you enough time in the case I described above, tell the same if you don't have the time to write down the design or the docs. If they insist the software must get finished sooner, explain to them the repercussion of omitting the steps you plan to omit, so that when shit hits the fan, it's on them.

I think better in code

This is the trap I myself used to fall into more often than I care to admit. You start writing your "design" by explaining which class goes where and which methods it has and... five minutes in you realize writing all that in code is more concise anyway, so you abandon the idea and start programming.

The cause for that is your design is too detailed on the code and not enough on the purpose and goals. The more of the design you can write without having to rely on specific details of an implementation, the more robust your application will be and, as time passes and technologies come and go, what your app is supposed to do remains clear and in human language. That's not to say there's no place for code in the design. The detailed interface is good to have and larger software should have its guts designed too. However, try to write your design as something you'd give to a competent programmer to implement, rather than step-by-step instructions that even an idiot could follow and end up with a program.

To give you a real-world example: 8–10 years ago, the biggest argument I had with other web developers was the width of the website. You see, 760–780 pixel maximum width was the golden standard, because some people had 800x600 monitor resolutions and so, if you account for the scrollbar's width, the 780 pixel website fit perfectly without horizontal scrolling. I was of the opinion that it was time for those people to move on to higher resolutions, and often used 900 pixel widths... or even 1000px, when I was feeling especially rebellious.

Now, imagine implementation-specific design docs that address that detail: "The website must be 780 pixels in width." Made sense in the past, but is completely ludicrous today. A better phrasing should've been "The website must avoid horizontal scrolling."

The benefits

Along with the aforementioned benefits of having a written design document, there are another two that are more obvious: tests and user documentation.

A well-written and complete design document is the human-language version of decent machine-language tests. It's easier to do TDD (Test Driven Development), which we'll do in the next post in this series, and your tests are less reliant on the specifics of the implementation, so that they don't falsely blow up every time you make a change.

Also, a huge chunk of your design document can be re-used for user documentation. We'll see that first-hand we we get to that part.

The Design

By this point, we have two groups of readers: those who are convinced we need a design and those who need to keep track of the line count of their programs to cry about when they have to rewrite them from scratch, (well, three groups: those who already think I'm an idiot).

We'll pop open DESIGN.md that we started in Part 1 and add our detailed design to it.

Throw Away Your Code

The best code is not the most clever, most documented, or most tested. It's the one that's easiest to throw away and replace. And you can add and remove features and react to technology changes by throwing away code and replacing it with better code. Since replacing the entire program each time is expensive, we need to construct our program out of pieces each of which is easy to throw away and replace.

Our weather program is something we want to run from a command line. If we shove all of our code into a script, we're faced with a problem tomorrow, when we decide to share our creation with our friends in a form of a web application.

We can avoid that issue by packing all functionality into a module that provides a function. A tiny script can call that function and print the output to the terminal and a web application can provide the output to the web browser.

We have another weakness on the other end of the app: the weather service we use. It's entirely out of our control whether it continues to be fast enough and cheap enough or exists at all. A dozen of now-defuct pastebin modules I wrote are a testament to how frequently a service can disappear.

We have to reduce the amount of code we'd need to replace, should OpenWeatherMap disappear. We can do that by creating an abstraction of what a weather service is like and implementing as much as we can inside that abstraction, leaving only the crucial bits in an OpenWeatherMap-specific class.

Let's write the general outline into our DESIGN.md:

# GENERAL OUTLINE

The implementation is a module that provides a function to retrieve

weather information. Currently supported service

is [OpenWeatherMap](www.openweathermap.org), but the implementation

must allow for easy replacement of services.

Details

Let's put on the shoes of someone who will be using our code and think about the easiest and least error-prone way to do so.

First, how will a call to our function look like? The API tells us all we need is a city name, and if we want to include a country, just plop its ISO code in after the city, separated with a comma. So, how about this:

my $result = weather-for 'Brampton,ca';

While this will let us write the simplest

implementation—we just hand over the given argument to the API—I am not a fan

of it. It merges two distinct units of information into one, so any

calls where the arguments are stored in variables would have to use a

join or string interpolation. Should we choose to make a specific country

the default one, we'd have to mess around inspecting the given argument

to see whether it already includes a country. Lastly, city names can

get rather weird... what happens if a user supplies a city name

with a comma in it? The API doesn't address that possibility, so my choice

would be to strip commas from city names, which is easiest to do when it's

a separate variable. Thus, I'll alter what the call looks like to this:

my $result = weather-for 'Brampton', 'ca';

As for the return value, we'll return a Weather::Result object. I'll go over

what objects are when we write the code. For now, you can think of them as

things you can send a message to (by calling a method on it) and sometimes get

a useful message back in return. So, if I want to know the temperature, I can

call my $t = $weather-object.temp and

get a number in $t; and I don't care at all how that value is obtained.

Our generic Weather::Result object will have a method for each

piece of information we're interested in: temperature, information on

precipitation, and wind speed. Looking at the

available information given by the API, we can merge

the amount of rain and the amount of snow into a single method, and for wind

I'll only use the speed value itself and not the direction, thus a potential

use for our function could look like this:

printf "Current weather is: %d℃, %dmm precip/3hr, wind %dm/s\n",

.temp, .precip, .wind given weather-for <Brampton ca>;

Looks awesome to me! Let's write all of this into our DESIGN.md:

# INTERFACE DETAILS

## EXPORTED SUBROUTINES

### `weather-for`

my $result = weather-for 'Brampton', 'ca';

printf "Current weather is: %d℃, %dmm precip/3hr, wind %dm/s\n",

.temp, .precip, .wind given $result;

Takes two positional arguments—name of the city and [ISO country

code](http://www.nationsonline.org/oneworld/country_code_list.htm)—to

provide weather information for. The country is optional and by default is

not specified.

Returns a `Weather::Result` object on success, otherwise returns

a `Failure`. The object provides these methods:

#### `.temp`

say "Current temperature is $result.temp()℃"

Takes no arguments. Returns the `Numeric` temperature in degrees Celcius.

#### `.precip`

say "Expected to receive $result.precip()mm/3hr of percipitation";

Takes no arguments. Returns the `Numeric` amount of precipitation in

millimeters per three hours.

#### `.wind`

say "Wind speed is $result.wind()m/s";

Takes no arguments. Returns the `Numeric` wind speed in meters per second.

Great! The interface is done. And the best thing is we can add extra methods to the object we return, to add useful functionality, which brings me to the next part:

Overengineering

It's easy for programmers to overengineer their software. Unlike building a larger house, there's no extra lumber needed to build a larger program. And it's easy to fall into the trap of adding numerious useless features to your software that make it more complicated and more difficult to maintain, without adding any measurable amount of usefulness.

Some examples are:

- Accepting multiple types of input (Array, Hash, scalars), just because you can.

- Returning multiple types of output, just because you can figure out what is most likely expected, based on the input or the calling context.

- Providing both object-oriented and functional interfaces, just because some people like one or the other.

- Adding a feature, just because it's only a couple of lines of code to add it.

- Providing detailed settings or configuration, just because...

Note that none of the above features are inherently bad. It's the reasons for why they are added that suck. All of those items make your program more complex, which translates to: more bugs, more code to maintain, more code to write to replicate the interface should the implementation change, and last but not least, more documentation for the user to sift through! It's critical to evaluate the merits of each addition and to justify the extra cost of having it included.

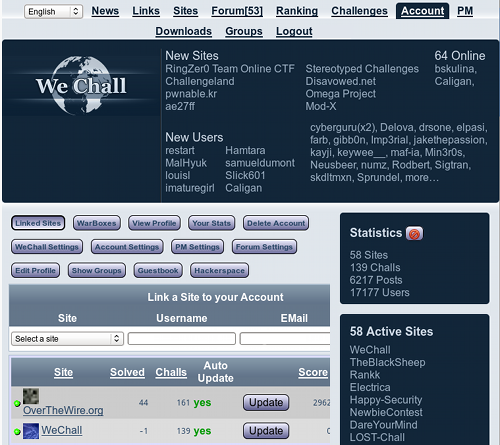

My favourite example of overengineering is WeChall wargaming website. I'm pretty sure there's a button that will make that site mow my lawn... I just have to find it first:

If I have some "cool" ideas for what my module XYZ can do, I usually simply make sure they're possible to add with my current design, and then... I leave them alone until someone asks me for them.

An astute reader will notice our weather-for can only do metric units

or that the wind speed doesn't include the direction, even

though the API provides other units and extra information. Well, that's all

our fictional client asked for. The code is easy to implement and the

entire documentation fits onto half a screen.

If in the future weather-for needs to return Imperial units, we'll simply

make it accept :imperial positional argument that will switch it into

Imerial units mode. If we ever need wind direction as well, no problem,

just add it as an extra method in Weather::Result object.

Do less. Be lazy. In programming, that's a virtue.

Our Repo

Our repository now contains completed DESIGN.md file with our design.

Commit what we wrote today:

git add DESIGN.md

git commit -m 'Write detailed design'

git push

I created a GitHub repo for this project, so you can follow along and ensure you have all the files.

Homework

Amend the design to include either of these features (or both):

(1) make it possible for weather-for to use both metric or Imperial units, depending on what the user wants; (2) Make it possible to give weather-for

actual names for countries rather than ISO country

codes.

If you're feeling particularly adventurous, design a Web application that will use our module.

Conclusion

Today, we've learned how to think about the design of software before we create it. It's useful to have the design written down in human language, as that's easier to understand and cheaper to change than code. We wrote the design for our weather applications and are now ready to get down and dirty and start writing some code. Coming up next: Tests!

Update: Part 3 is now available!

I blog about Perl.

I blog about Perl.

Leave a comment